Heinz Insu Fenkl, some years ago, wrote an interesting paper, “Asian American Literature and Korean Literature: Common Problems and Challenges from a Segyehwa Perspective.” The paper works in and around the kind of problems I currently see in some Korean Translation – that as a literature already suffering from the asymmetricality inherent in being a smaller language and smaller culture cannot waste its “shots” when it is trying to send literature over the great cultural and hegemonic divide. The author is explicitly comparing Korean translated literature to the literature of Korean American and says about the latter:

In the process of moving from the margins to finding their tenuous place in the problematic contours of the mainstream, Asian American writers have faced particular and complex challenges. These generally have to do with making their own cultural experience and relationship to language(s) not only comprehensible and meaningful, but also aesthetically interesting and artistically legitimate to a readership which is predominantly white and English-speaking — these are issues that might be considered issues of cultural and linguistic translation.

(emphasis mine)

As the article notes, there is a lot to wrestle with in this question. To what extent does “making (cultural experiences) … comprehensible and meaningful” run the risk of denaturing that culture? Certainly the history of Asian literature suggests that uncomfortable trade-offs might be necessary at the start – Juvenalia and pandering, unfortunately, always seem to sell. And Heinz is worried about “cultural imperialism” in a way that I am not. He says, “it is Koreans who should rightfully maintain control over representations of Koreanness to the world. Korea needs to participate actively in the creation of meanings given its representations abroad, and that entails that Koreans themselves be particularly discerning about how such meanings get reflected back as transformative elements in local Korean culture.” I take this to be half right and half wrong. Korea certainly needs to be in charge of the creation of meaning surrounding its cultural contents, but it needn’t worry, at least quite yet, that these representations will be reflected back in any distorted or harmful way. Unfortunately, my certainty here is based on the fact that light has to go out in order for light to reflect back, and currently that

broadcast is largely failing for Korean literature.

The good news is, I suppose, that if Heinz is correct, Korean American writers have done some of the ice-breaking, and the atmosphere in which Korean literature will eventually be received should be less orientalized and infantalized than it was in the past.

And, in any case, the correct answer to many these problems is to determine what the western audience constitutes as appropriate (a step that translation currently seems to be lacking, with even more books about Korean separation trauma following their traumatic predecessors into that greatest trauma of all – for literature – oblivion) and then decide what can be translated to hit that sweet spot that ALSO fits the goals of Korean translating institutes.

Heinz goes one step further, though, and it is a step I am still pondering.

that government and academy actively support translation projects but let the translators themselves select the works based on passionate personal interest and commitment. A translator with free rein and personal motivation will always do a better job than one who works under the funding and editorial control of some organization (no matter how significant that funding may be).

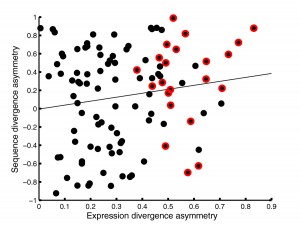

I am partly pondering this because many of the early, and in retrospect horrible translations, were done by the sort of autodidactic chap that Heinz seems to favor here. But, to a greater extent I feel that this step is not consistent with Heinz original argument that Korea should be in charge of its cultural contents. First, the foreign translators would have slipped the leash – that might be good or bad, but it certainly would not keep control with Korea. Second, I would forsee difficulty for Korean translators in getting published as compared to foreign translators. This asymmetry, I fear, would only grow.

Heinz comes back to sentiments with which I entirely agree when he concludes:

Korea will only be able to contribute the valuable lessons in its literature to the world once it understands the complex dynamics of translation. The burden in this is not on the original writers, nor should it be on the academy or some government ministry — it should be upon the translators to adequately address the issues of language, culture and aesthetics.

Because this is true – If cultural content should be chosen by the culture, why shouldn’t translation be handled by the translators? The cultural arbiters, of course, have the right to judge, but perhaps they should let Heinz’ model have a shot, because it might just do better than the model we are currently employing, which has yet to create a signature hit. Let translators finish all the works of Yi Mun-yol and Kim Young-ha. Lord knows, translators probably don’t want to have to work on the 10th translation in 60 years of “Buckwheat Season.”