(A version of this piece originally appeared in Yonhap News)

(A version of this piece originally appeared in Yonhap News)

If most people are asked to imagine early rappers, they most likely do not conjure up the picture of a Korean man, dressed in humble clothes, sheltered from the rain by no more than a straw hat, walking across Korea with a staff, finding his lodging and food based on the wit, and sometimes ferocity, of his rhymes. And yet, Korean poet Kim Sakkat could well be called the original rapper/battle-rapper.

Kim Sakkat (birth name Kim Pyong-yon), was born in 1807. With the disgrace of his grandfather as a result of the Hong Kyong Nae insurrection, Kim’s entire clan was disgraced. Kim and his brother were taken to live, in semi-obscurity, in the house of a family servant. Eventually, Kim returned home, got married, and had a son. About that time, he embarked on the life of a wanderer. Some speculate that this was due to financial difficulties, but the more literary story is that his poetic skills caused him to enter a poetry contest that he won in which he accidentally attacked the memory of his grandfather. Ashamed of this impiety, he relegated himself to a life of wandering.

In either case, from that time on Sakkat lived the life of an outcast. His son tracked him down three times, but three times Sakkat managed to slip away.

Sakkat was often forced to rhyme for his dinner or lodging, and it is here that he first revealed his skill as perhaps the world’s first ‘battle-rapper.’ When challenged, Sakkat would frequently respond with poems that meant one thing in Chinese (the language of literature at the time) and quite another thing, usually insulting, in Korean. Rather Richard Rutt notes, “the insulting poems could be interpreted as symbols of the spirit of revolt that may be supposed to smoulder in the breast of every Korean, constrained as he is by a highly conventional society.” (66)

Once, challenged by a village schoolmaster to write a poem for his evening lodging, Sakkat faced a different kind of problem. The schoolmaster, intending to deny Sakkat lodging, challenged Sakkat to write a poem in which the first line ended in the unusual character, myok. Kim responded:

Of all possible rhymes how did you find myok?

The schoolmaster, cruel and still intending to deny Sakkat lodging, demanded the character myok also be used to conclude the second line. Sakkat responded:

The first was hard enough to find, much more this second myok.

Once more, the schoolmaster requested a line concluding in myok.

If a night’s lodging depends on this myok….

Predictably, the vindictive schoolmaster again asked for a line ending in myok and, predictably, Sakkat responded:

Maybe a rustic schoolmaster knows nothing else but myok?

These are clever uses of myok, with the first usage using the character just as the schoolmaster does – as a character without any contextual meaning. Yet, as the poem continues the character has useful meanings in the poem:

Of all the possible rhymes how did you find (the character) myok?

The first was hard enough to find, much more the second to seek and find.

If a night’s lodging depends on this seeking and finding,

Maybe a rustic schoolmaster knows nothing else but (seeking and finding OR the character itself) myok?

Kim Sakkat’s second amazing extemporaneous skill was to compose simultaneously in Korean and Chinese and it is here that his link to battle rap becomes explicit. Because the languages share sounds and words, it is possible to write a poem in one language that has an entirely different meaning in the other language. This is a tremendously complicated process though, for each word and each sentence must make sense in both languages. The most famous of Kim’s ‘double’ poems was composed at a wedding at which Kim was apparently upset with the host. In Chinese, Kim wrote a semi-clichéd piece of work (All translations here are by Richard Rutt):

The sky is wide, beyond imagination,

The flowers fall and the butterflies come no longer

Chrysanthemums bloom in the cold sand,

The shadows of their stalks lie on the ground,

The poet passes the waterside arbour

And slumps in drunken sleep under a pinetree.

The moon moves, the mountain shadows shift

The merchants return home with their gains

This is a rather flat reflection on the passage of time. But when read aloud and understood in Korean, the poem takes on an entirely different meaning:

There are spider’s web on the ceiling,

Bran is scorching on the stove:

There’s a bowl of noodles

And half a dish of soy sauce

Here are some puffed grain and cakes

Jujubes and a peach.

Get away you filthy hound!

How that privy stinks!

What was a series of bland clichés is turned into an attack on the hospitality and cleanliness of the host. This kind of dual-language improvisation is a remarkable skill, and one that is not much found elsewhere in literature. Sakkat’s fame as a wit is so great that clever verses of unknown origin are often attributed to him.

John Eperjesi, an Assistant Professor in the School of English at Kyung Hee University, notes, “Like all great MCs, Kim Sakkat was a rhetorical trickster who used humor, puns, irony and repetition to defeat his opponents. And the stakes were sometime high. In one battle, the losing poet had to have a tooth pulled out. It’s fortunate that Sakkat had good linguistic skills or he might have been remembered as the toothless poet.”

Sakkat was capable of lesser tricks as well; he sometimes wrote poetry in which the shape of Korean letters gave the poem meaning:

Stick a K in your belt.

Put NG in your ox’s nose

Go home and wash your R,

Or else you’ll dot your T

When the shapes of the Korean letters are taken into account the poem becomes clear. The Korean letter K is shaped like a sickle [ㄱ], NG is a circle [ㅇ], R [ㄹ] is the same as the Chinese character for self, and T [ㄷ] needs only the addition of a dot at the top to become the Chinese character for death

Stick a sickle in your belt.

Put a ring in your ox’s nose

Go home and wash yourself

Or else you will die.

That example might not reach to the sublimest heights of poetry, but Kim was also capable of achieving sublime effects. Korean poetry often includes repetition and the following verse takes advantage of that:

White sand, white gulls, all white, so white,

I cannot tell white gulls from sand

A fisherman sings out, and away they fly:

Now I see the sand is sand and the gulls are gulls.

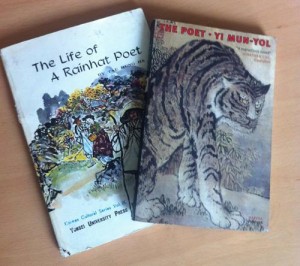

Kim Sakkat has been memorialized in literature as well as history. In 1969, playwright Tae Hung Ha published a play entitled The Life of the Rainhat Poet, which follows Sakkat’s life from his early understanding of his compromised position in society to his eventual death. Sakkat was also memorialized by one of South Korea’s most internationally well-known writer, Yi Munyol in his 1992 novel, The Poet.

The Website Daily Korean Stuff reveals that Sakkat is still extremely popular in Korea, where several stores, restaurants, and even a Soju brand are named after him.

An English translation of Kim’s poetry can be found on Amazon and today Sakkat’s legacy lives on in the work of modern rappers, including battle-rappers such as the Korean American Dumbfoundead and other rappers such as Korean rapper Loptomist.

For more excellent biographical info, hop over to that Daily Korean Stuff link!