“Wearing that coat, you look like an amateur spy.”

I Could Use an Angel

(John Hiatt)

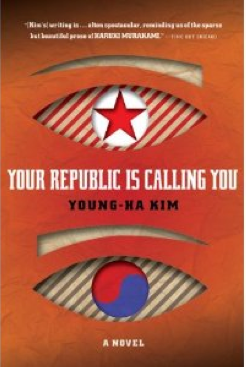

Kim Young-ha’s “Your Republic is Calling You,” has a decent chance to be a breakthrough Korean novel in English. Kim, who has shown brilliant flashes in his past works, creates his most integrated and human work here – this is the work of an author who has substantially mastered his themes and tools. The story, a web really, reveals the clandestine agent common to humanity through the tale of one particular spy and his family.

Intricately plotted and multiply narrated, “Your Republic is Calling You” begins a bit angularly, as if Kim is trying to work too many things into too little space. There is lots of expository internal-monologue revealing histories, judgments, and nostalgic presentations of past events.

The book quickly settles down however, and as it focuses on characters for longer periods of time, it catches its stride. At about 20 pages in author Kim takes a breath, and the book itself breathes.

The plot is deceptively simple – it follows one day in the life of a North Korean spy who is apparently being called back home.

This call unravels his life in ways that are predictable and unpredictable.

The “spying” metaphor is at the heart the book as all its characters are, one way or another, undercover. It is one of Kim’s skills that he reveals in a matter-of-fact fashion the difference between the public images of his characters and the lives they lead in their heads, in seedy motel rooms, prosaic offices, schools, and even in shootouts on the beach. Kim never shows his cards early, and as he makes each reveal, the tension and angst increase. By the end of “Republic,” the undercover agent in each character has been exposed and each character squirms in the unexpected light.

Readers of Kim’s previously translated works will see much here that is familiar and comfortable. Kim’s writing is semi-existentialist, internationally oriented (his “North Korean” protagonist imports foreign films and drinks Heineken), and socially modern. These have always been features of Kim’s writing that has recommended it to me, but at times in previous works, particularly in some passages of “I Have The Right To Destroy Myself,” (reviewed here at KTLIT) Kim has seemed to be trying these approaches on for size, not entirely certain how to internalize them. This is, of course, the process of growth in an author, and in “Republic” this growth has borne fruit. In this book, with one exception, Kim’s themes and internationalization seem integral to the story and flow seamlessly within the plot.

I got an x-ray camera hidden in your house

That sees what I can’t see

And that man you were kissing last night

Definitely was not me!

I Spy For the FBI

(John Hiatt)

That one exception is my other slight cavil with “Republic.” Kim works in a strongly sexual vein in this work and at the outset of the book he has a sexscene that does not seem completely integrated into the story. The scene seems hurried in just to get a sex scene in. This quickly introduced and then discarded scene had the unfortunate effect of making me initially distrust the critically important sex-scene that slowly comes into being through the second half of the book. And this later scene provides one of the most “undercover/revealing” moments in the book.

This is a trivial complaint about a work that kept me riveted as it went along and Kim has also, to some extent, stepped back into more ‘traditional’ modern Korean themes as this “Republic” is strongly premised on issues of separation. Kim Jae-gon (KTLIT’s Korean contributor), did a quick translation of a Korean review (from the 한겨레 ) of this work that noted Kim Young-ha’s theme:

Ki-young was born in 1963 and sent to South Korea in 1984 and now gets the order to return to home. His 42years of life is divided into two 21-year-long periods in two countries. The inner conflict about whether he follows the order is also the one between the former life of North’s 21-years and the latter life of South’s 21-years. The agony of struggling 24-hours implies his complete 42-years of life, or the division of 60 years between two Koreas.

Interestingly, that review also comments on Kim Young-ha’s sexual themes, but focuses on the sex that betrays a marriage vow, rather than a random hookup between a young woman and an older man for a bit of semi-not-really-consensual urination (noted above). To my western eye, the latter seems much less likely than the former and it is revealing that a Korean reviewer would focus on what to me is the much more likely event.

Kim’s writing is razor-sharp. Any reader who has been faced with the threat of loss will recognize Kim’s description of the “premature nostalgia” that such a threat engenders. His writing about this general condition is specific and clever. A good example of Kim’s specific descriptive ability is when he describes the illicit but often silly (and still dead-serious) thrill that comes with youthful rebellion:

For Southern youth in their early twenties, having been indoctrinated in anti-Communist education in schools, speaking this way felt vulgar, much like hearing a prim woman refer to a penis as a cock. At first, it was difficult for them to refer to the two heads of state as Dear Leader or The General, but once they did, they shivered with the excitement that came with breaking the law.

That’s a passage that brilliantly outlines the borders and overlaps between “Big R” rebellion and the “Little R” rebellion of all young rebels. “Republic” is full of this kind of brilliant writing.

Which leads to a word related to translation: Kim Chi-young, who translated “Republic,” has done a job that even surpasses her previous excellent translation of “A Toy City.” Kim Chi-young is one of the few translators whose name alone, on a dustcover, would persuade me to purchase an unknown book. I counted exactly two instances in which I wondered at a phrase, and that would be a low number for a book written by an English author in their native language. ^^

As a novel, “Your Republic is Calling You,” is a triumph, but it could also be important on a larger scale. It is notable that this was NOT translated through the traditional Korean national translation institutions. This means, wonderfully, that it does not seem to have been chosen in order to show “representative” Korean culture or history. This work was chosen for translation because it is interesting to potential readers, not for pedagogical reasons. Above and beyond my respect for Kim’s work in general, and this work in particular, I root for its success hoping that such a success could open up the eyes of Korea’s national translation institutions to the opportunities in translation.

This is an outstanding book and as the important threads tie together at the conclusion it moves at relentless speed. “Your Republic is Calling You” is taut, engaging, ironic, scathing, brutal and resigned in turns. The last 40 pages are exceptionally tightly written and the screws tighten, page by page, as life and a history of subterranean decisions conspire to strangle the lives of all the “agents” of the story.

In a brief coda Kim leaves us with a vision of a “new day” that can be read as ironic, hopeful or merely repetitive – In a world where everyone is a tout and ‘hopeful’ is lagging at the rail.

Buy this one. It comes out in September and can be ordered now.