Cho Chong-hui’s The Cry of the Harp is a one-author collection in the “Other Korean Short Stories” series published by Si-sa-yong-o-sa . Translated by Genell Y. Poitras (what a great name!) it contains the novel for which the collection is named, as well as Chom-nye, The Ritual at the Well, and Round and Round the Pagoda. The book is out of print, but can be found second-hand on Amazon, though it is often shockingly expensive (Currently it inexplicably ranges from $5 to $107.37 on Amazon!).

The title story is is autobiographical, related Cho’s own experiences as she and her family, semi-succesfully, navigate the stressful era’s of Japanese colonialism and then the utter confusion surrounding the taking and re-taking of Seoul during the initial stages of the Korean War. Cho seems relentlessly honest, often portraying herself as a harridan. She seems a harridan at least partly in contrast to her husband, the poet Pa-in, who is a sometimes ineffectual intellectual, but always more easy-going than Cho. About two chapters in, one possible reason for Cho’s tense attitude is revealed, but I leave it to the reader to discover that.

Going broke and nearly starving in Seoul, the family moves to the countryside and begins to fashion themselves into gentleman farmers. This section has some comic elements, as the countryside does not come naturally, particularly to Pa-in. They do settle into a nice groove, but ascolonialization ends, Pa-in moves back to Seoul with the intent of re-establishing his literary career. Pa-in’s optimism at this time is nearly painful to read, for those aware of what Korea, and he, are about to go through.

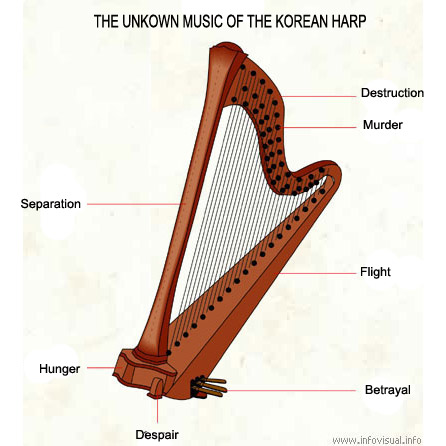

Once in Seoul the political problems begin. Pa-in is incorrectly associated with a political group, and this gets him in trouble with the government. Worse, when liberation comes, Pa-in is branded a collaborator, and has his civil rights removed. Then comes civil war and even those who don’t choose sides are assigned them, and as the tides of war ebb and flow across Seoul. Cho relates her own, coldly terrifying, tale of former friends and colleagues turning against each other, leavened only slightly by one or two friends who remain faithful, even with differing ideologies. Pa-in is called in by the government for questioning and is never heard from again. This section of the book directly brings home the feelings of insecurity (as well as hunger and pain) caused by the Korean War. Then, as the tides of war change again, most of the remaining family is once again forced to leave Seoul, and suffers at least two more separations along the way. One of the moving scenes is eerily reminiscent of that in Yang Kwi-ja’s A Distant and Beautiful Place.

The story ends on a reflective note that is bitterly nostalgic in a way that you might not guess from Cho’s initial portrayal of her own, younger, self. The Cry of the Harp is a particularly good novel for those attempting to learn what the shifts in political and military tide did to ordinary citizens of Korea. In many ways this reminded me of Park Wan-suh’s “Who Ate Up all the Shinga,” but a bit shorter, less dense, and all around easier to read.

Chom-nye is a more overtly political story, comparing the brief and unfortunate life of its title character to the much more be-starred life of the daughter of the local ex-landlord. It contains some scathing passages which portray the social schisms between rich and poor – while landlords and yangban may have been officially replace, nothing much has changed, in fact social superiors have even been elevated to the statuses of Gods whose mere presence can turn villagers to something like stone:

Although they had done nothing which deserved a scolding they could only hang their heads and remain silent. The words would not come.

No one knew when this had all started. Generation after generation watched and learned; the grandfather, the father, and the son, each learning from the one before. (132)

The plot turns on a detail as small as a chicken, and pretty much everyone comes off poorly.

The Ritual at the Well is a sad and funny story about a village undergoing change it can barely understand. The narrator gets progressively crankier while drinking makgeolli and observing thick headed neighbors, The Ritual at the Well also contains a message similar to that of Chom-nye, that while the old social order has putatively been destroyed it has in fact merely been replaced with a newer, even more arduous one. One of the centerpiece descriptions (of which there are several during the story) is a harrowing description of waiting for spring and the opportunity to eat grass. The ritual, of course, stands for everything about to be lost, and it is no coincidence that the ritual founders because of the introduction of something western, in this case wheat-based bread.

Round and Round the Pagoda, honestly confused me. It contains a lot of expository text about who met whom and who is related to whom and it skids over decades at a time. It is also the least well written of the pieces in this book, and by the end it, when the narrator was dizzy and about to die, I felt just about the same way.^^

The confusion of the last story, however, is no reason not to get this book if you can find it. The other stories are well told and taut, and heaps of cultural knowledge are painlessly contained in them. The novella The Cry of the Harp, in particular, is a brilliant description of the tension of an era.