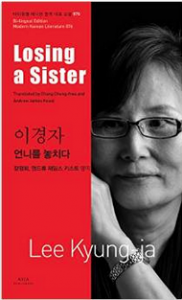

Losing a Sister by Lee Kyung-ja focuses on one particular theme of Pundan Munhak (Separation Literature), that of the re-unions between families split by the war. This territory has been covered in other works including Yi Mun-yol’s An Appointment with my Brother, and more indirectly in Sonu Hwi’s One Way, but Losing a Sister takes a particularly personal and specific non-macho approach to the subject.

Losing a Sister by Lee Kyung-ja focuses on one particular theme of Pundan Munhak (Separation Literature), that of the re-unions between families split by the war. This territory has been covered in other works including Yi Mun-yol’s An Appointment with my Brother, and more indirectly in Sonu Hwi’s One Way, but Losing a Sister takes a particularly personal and specific non-macho approach to the subject.

Losing a Sister is based on the infrequent state-sponsored meetings between families separated by the Korean War, the last one in 2014, and the previous one in 2010. In this story two sisters, Se-hee in the North, and Myeong-hee in the South, have a short window to meet each other, within the context of a highly managed political and PR event.

The sister’s were initially separated when Se-hee, strongly political, moves to the North with the promise to her sister that she will return before a bag of rice in the house can be finished. War and separation make this impossible. Myeong-hee is almost literally trapped in amber by this situation, unable to get past it, and alienated by the separation and where it took her life.

The sisters meet several times across the events, but Myeong-hee is so alienated that she has trouble connecting with her sister, a process that is complicated by the fact that Se-hee has a tendency to parrot a kind of party line, particularly about Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. Lee also shows partially observed snapshots (from Myeong-hee’s perspective) of some of the other families that are re-united, and this both reinforces and puts Se-hee’s experience in contrast. Se-hee’s experience, in many ways, only amplifies the pain of separation and when, at the end, Se-hee finally figures out what has happened (and perhaps what should have happened), the fact of separation, physical, personal and emotional is too vast to overcome.

Lee’s skill at personalizing the bigger issue into a pair of sisters, and at showing how great the emotional and psychological gulf can become in a split family in a split state, makes this story engaging as a story of two sisters, but also clearly outlines the larger political and historical situation in which the story sits. The translation by Chang Chung-hwa and Andrew James Keast has a few oddities at the outset (“lenitive?” Really?) but settles in to nice readable prose. As usual in this series, there is bilingual text, biography, criticism, and summary at the end, which will be useful for those unfamiliar with the historical background of the book, but again, Lee’s writing here is so good that she introduces most of that easily as she goes.

Another good one from the ASIA Publishers Modern Korean Literature series.