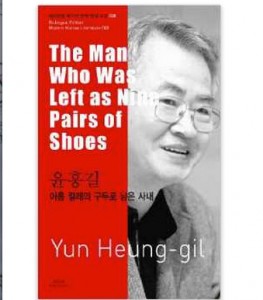

There may be a real order to which Korean literature should be read, and although I’m sure I’m not clever enough to map it out, re-reading The Man Who Was Left as Nine Pairs of Shoes (아홉 켤레의 구두로 남은 사내), reminds me that it might exist, because the first time I read this story I completely missed part of its point, partly, perhaps, because I did not read it as in individual work,

There may be a real order to which Korean literature should be read, and although I’m sure I’m not clever enough to map it out, re-reading The Man Who Was Left as Nine Pairs of Shoes (아홉 켤레의 구두로 남은 사내), reminds me that it might exist, because the first time I read this story I completely missed part of its point, partly, perhaps, because I did not read it as in individual work,

The first time I read this work it was in the excellent collection Land of Exile Contemporary Korean Fiction, and in the company it was in, it seemed relatively insignificant to me as I merely noted,

Yun Hunggil’s The Man Who Was Left as Nine Pairs of Shoes implies that anyone can become collaborator – the unfortunate character of the title notes that “There are times when you can do something you wanted absolutely no part of, and not even realize it …Just because you haven’t cooperated [with the police] in the past doesn’t mean you won’t cooperate [with the police] in the future”

Which, let’s face it, I just didn’t find as amusing as Kapitan Ri, by Chon Kwangyong, which tells a similar collaborator story but in a much funnier form, and neither did I catch the Nine Pairs of Shoes’ trenchant social commentary on my first reading. Reading Nine Pairs of Shoes by itself, and with some excellent critical commentary (which is not always present in these Asia Publishers stories) renders it an entirely deeper meaning.

It is the story of the O family, which outspends its means and rents a room out to a certain Mr. Kwon who immediately comes with several additional burdens including a pregnant wife, impecuniousness, and a very bad reputation with the police as he is an ex-con. One of Kwon’s strange habits is his daily polishing of shoes, pairs of shoes that seem above the level of his shabby existence. Shortly , it is revealed that Kwon is political rebel and moral to the point of sometimes silliness (getting fired as an editor for continually insisting that grammatical errors be changed, even though the authors want them in). He is, in a word, trouble, and quickly becomes jobless. As the story continues, the policeman Yi continues to pester the landlord to report on Kwon, and Yi continues to claim that this kind of spying is neither his job, nor his right.

O has an interesting series of ruminations on Dickens vs. Lamb and the “proper” attitude towards the poor, which is really the heart of the story as Mr. O and Mr. Kwon represent different and partially opposed stances towards class differences, both quite proud of their educational statuses, but Mr. O is a relentless social climber towards the intelligentsia/status/riches, while Mr. Kwon, despite they symbol of his spotless shoes (his last sort of gesture towards ‘middle-classness’) is a man on his way down the working-man totem pole (in fact the comments after the novella are quite clear and quite good about this).

So, reading it with a bit more knowledge and experience, it has become a much richer story to me. When Yun brings it all together with his stinging final punch line, a reader really feels it, and if you know a bit of history about the time, or even cheat and read the Afterword first, the story has all that much more depth.

Yun is a clever writer, apparently well translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, and, again, if you have a bit of cultural/historical knowledge you’ll really appreciate the cleverness of Yun’s writing.

Lines like Mr. O observing of his wife, “Already my wife was trying to act every stitch the landlady, just like the daughter-in-law who finally becomes the mother in law” are redolent with meaning to people who have lived in Korean culture or read many of these books, and coming back to this line after having read so many other books in between gave it a cultural meaning that I couldn’t imagine the first time I read this work.

A great work either way though, as it tenaciously probes the political and economic tensions brought about by the post-war reconstruction.

The story ends on a finished yet unfinished note, and in the Afterword it was interesting to read that it is the first work of a trilogy. I hope that someone, somewhere, is toiling away on the remaining two novellas.^^

I should also note that this same translation, by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, can be found free, online at the Korean Journal (by downloading the PDF on this page) but it is much more difficult to read, does not have the original Korean, and lacks the rather good historical and critical essays that this particular volume of the Asia Publishers Series has.

Hyun has also had The Rainy Spell translated, which KTLIT reviewed here.

Paperback

Publisher: ASIA Publishers (2012)

ISBN-10: 8994006281

ISBN-13: 978-8994006284

NOTE ABOUT THE COLLECTION

There are actually four collections here, “Bi-lingual Edition Modern Korean Literature Volume One”, Volume Two, Volume Three, and volume Four has just been published. The collections are of 15 small volumes each, and each collection is broken into topics with the first collections comprising Division, Industrialization, and Women; the second comprising Liberty, Love, and North/South, and; the third collection comprising Seoul, Tradition, and Avant Garde (can’t say about the fourth collection as I haven’t yet seen it)

In addition, each story comes with a kind of critical summary, several bits of critical analysis, and a biography of the author. When these pieces are put together, it makes the stories much easier to read, as the necessary cultural and historical background is neatly presented to the reader.