Yeesh, first draft done (BTW, none of this draft would have been possible without the awesome, AWESOME work of my student 윤재선, who someone should immediately offer a job^^).

Anyone who wants to tear it up, should feel free.^^

INTRODUCTION

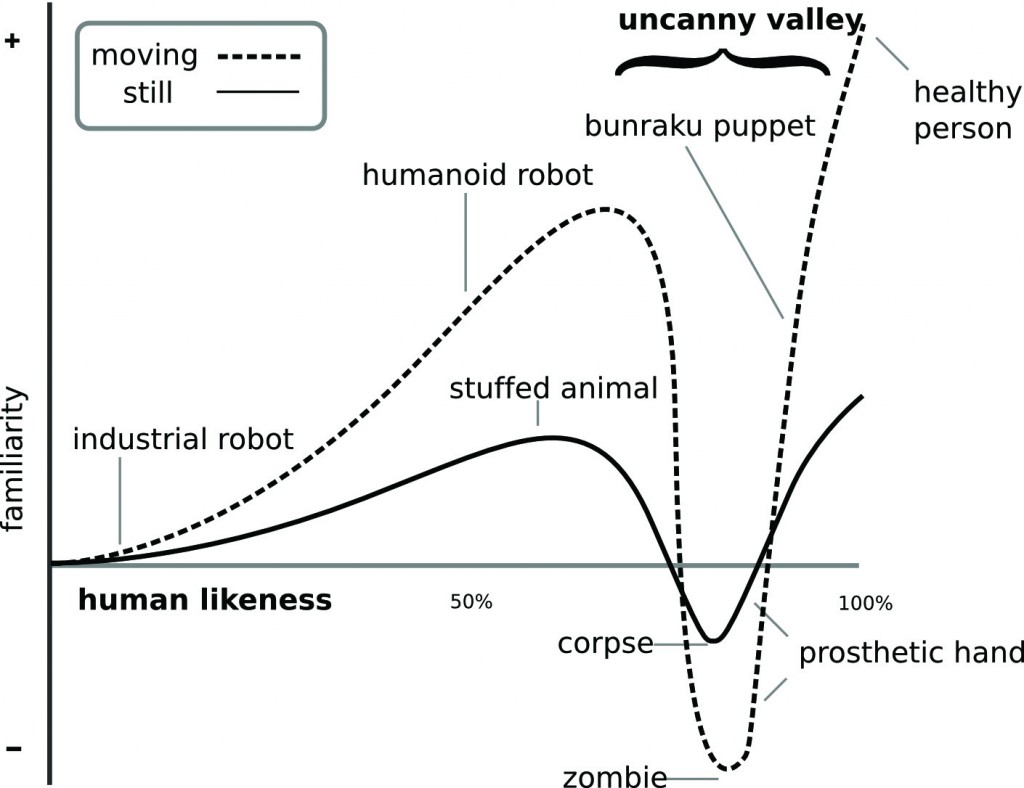

Katherine Reiss and Hans Vermeer’s Skopos Theory, developed at the end of the 1970s, argues that translations are mutable on the basis of the complicated interaction of a variety of factors, most of which add up to fulfilling the purpose of the target text. Just prior to this time, Japanese robotics professor Masahiro Mori proposed the theory of the “uncanny valley,” although at that time only in respect to the appearance of robots. Mori’s theory proposed that as a robot’s appearance becomes more human, human responses to that robot become more empathetic until a certain point at which a partial but incompletely similarity begins to arouse revulsion. Then, at a subsequent point of increasing similarity, to the point of exact similarity, emotional response again becomes positive. This theory can be abstracted to the argument that as any product (including translated literature) begins to move towards the cultural expectations of that product, it will be looked upon more favorably until that point at which it closely, but not sufficiently, mimics the cultural expectations of the cultural product; and, again, when it becomes equivalent to the expectations of that cultural product it will again be accepted favorably.

This paper will argue that by appropriating the target-text focus of Skopos Theory and understanding the dangers inherent in translation that leaves text in the “uncanny valley,” certain kinds of text, particularly genre-based texts, can be manipulated in translation to be both accurate to the original intent of the literature in its source text as well as to become “canny” in the target language.

This paper will consider a work translated by Kim Chi-young, Shin Kyung-sook’s Please Look After Mom as an example of successful Skopos/Uncanny Valley-avoidant translation processes. This paper will focus on four different aspects of a Skopos-based, uncanny-valley avoidant translation strategy: Proper word choice (this is admittedly, also a critical feature in more traditional translation strategies), addition of text to facilitate cultural understanding; alteration of text to facilitate cultural understanding, and, re-ordering of text in order to clarify narrative and/or facilitate a reader’s understanding of the text based on expectations of genre.

Finally, this paper will present some original research suggesting that the successful translation of genre fiction, such as Your Republic is Calling You, also fuels a generally increased success of translated fiction, including that which has not been translated with the goals of Skopos Theory in mind.

SKOPOS, UNCANNY VALLEY, AND SUCCESS

Skopos Theory was first proposed by Hans Vermeer in the 1970’s, as a reaction to established linguistic based translation theories which largely focused on the “’equivalence or ‘faithfulness’ to the source text as the most authoritative criterion to judge whether (a) translation is successful or not” (Du, 2012). Skopos is the Greek word for aim or purpose, and it was Vermeer’s argument that translation is “not only a process of transcoding, but a specific form of action, the purpose or skopos of which must be determined before translation begins (Al-Omar, 2012). The primary determinant of skopos can be simplified to the question, “how does the client plan to use the target text” (Anderson, 2011).

One of the ways in which authors, in general, for it could be argued that the act of writing itself is a form of translation, assist their clients in using texts is to put those texts into recognizable forms and genres. In the question of translation, from a Skopos perspective, this implies that the translator must translate all forms into the target text, beginning as much as possible at the level of vocabulary, continuing up through such concerns as sentence structure, context (high versus low) level of the culture, and even narrative form.

All of these levels include frames of reference which help target-text readers to “identify, select, and interpret texts” (Chandler, 2000) and particularly in genre-based fiction, are elements which are required to give readers assurance and guidance as to what can be expected in the work of genre fiction. Genre fiction, for the purposes of this paper, is understood to be “stabilized-for now” (Schryer, 1993) collections of approaches that help readers to understand texts. These approaches include “social relationships, represent contexts, and advance (or repress) particular social and political perspectives,” (Kain, 2005) and, critically, create accessibility for readers. Consequently, if one is to translate genre fiction, the question of accessibility, or understanding is the most important one

An article by professor Masahiro Mori, entitled “The Uncanny Valley” was published in the journal ‘Energy’ [DiSalvo, 2002]. This article included a graph that outlined how a human-like appearance or activity could affect human reaction to it (Fig 1).

While the Uncanny Valley has primarily been used as a model of human reaction to robot design, it has also been applied to psychological experiments (Minato et. al., 2004), sounds (Scheeff, 2000) and computer graphics (Beschizza, 2008). However, the Uncanny Valley is also a concept that should be considered when discussing translations of genre translations and their expectations.

If these theoretical grounds suggest that a Skopos-based, Uncanny-Valley avoidant approach to translation is best for genre-based translations, what can translators learn by looking at the work of Kim Chi-young, particularly her success in Please Look After Mom?

First, Kim is always careful to understand the implications of seemingly similar words in the target language. Consider the relatively simple Korean word 헛간, which has the general meaning of a structure for storing agricultural items. This means that in English, it can easily be translated into either barn or shed, and this would seem appropriated as far as the Korean is concerned. Barns and sheds, however are not always synonymous in English, and it is important to note that in Shin’s source text the idea is that small fruits and their products will be stored here.

The Korean text (Page 5, 11th line) reads:

헛간에는 엄마가 철따라 담가놓은 매실즙이며 산딸기즙이 담긴 크고작은 유리병들이 즐비했다.

Which Kim Chi-young translates to (Page 5 11th line):

In the shed, Mom kept glass bottles of every size filled with plum or wild-strawberry juice, which she made seasonally.

Names are another issue in this translation. Korean writing often does not spell out names of people or cities. Related, as characters are often described by relationship, names are relatively less important in Korean text. This, however, falls squarely in the uncanny valley in English. English, being a low-context language, requires the use of names and pronouns, and when such names are not provided, something seems slightly off to an English reader. In fact, authors typically use this non-naming, or initialized name to indicate something is subtly wrong. Perhaps the finest example of this is Franz Kafka who, who in his work “The Trial” intentionally uses the blandest and most common name imaginable for his protagonist (Josef K.) and then immediately reduces that name to the even more cipher-like “K” (Bradley, 2012). The reduction of names to initials is, to put a name to it, Kafka-esque, and consequently does not work properly when literally translated into English.

Similarly, the Korean use of relationships to denote character identification falls in the uncanny valley.

When Shin Kyung-sook writes (Page 10, 3rd Line):

오빠 집에 모여 있던 너의 가족들은 궁리 끝에 전단지를 만들어 엄마를 잃어버린 장소 근처에 돌리기로 했다.

(The family is gathered at your older brother’s house, bouncing ideas off each other.)

However translator Kim renders this:

The family is gathered at your eldest brother Hyong-chol’s house, bouncing ideas off each other.

In other words, 오빠 is expanded from “older brother” to eldest brother Hyong-chol.

In fact, each time a new character is introduced in the English version of Please Look After Mom, they are named, which is not true in the Korean

Translator Kim employs a similar tactic for city names. When Shin says, in the original (Page 11, 18th Line):

예전엔 생일이나 다른 기념할 일이 생기면 너를 비롯한 도시의 식구들이 J시의 엄마 집으로 이동하곤 했다.

(You and your siblings always went to your parents’ house in J city for birthdays and other celebrations)

Kim alters the text to (Page 4, 18th Lin:

You and your siblings always went to your parents’ house in Chongup for birthdays and other celebrations.

As in the case of proper names, this kind of addition is routinely made in the translation, when a town is mentioned.

Sometimes translator Kim combines these types of changes, removing the ‘foreign’ feeling of the initializations while also adding additional detail that might be inferred by a Korean reader, or even be considered unimportant by them. When discussing a shift in power/travel relations between the narrator and her mother, the original Korean reads (Page 12, 11th Line):

언제부턴가 도시 식구들이 J시에 가는 일보다 엄마가 아버지와 함께 도시로 오는 일이 많아졌다.

(At some point, the children’s trip to J city became less frequent, and Mom and Father started to come more often to a city/cities where the children live.)

Which is translated to (Page 5, 22nd Line):

At some point, the children’s trip to Chongup became less frequent, and Mom and Father started to come to Seoul more often.

Korean readers may guess that the children are living in Seoul, both because of other narrative aspects and a general cultural understanding that in Korea Seoul is the place to be, however this would not necessarily be apparent to a Western reader. In addition, in the original Korean a reader cannot determine whether what the Korean author means by 도시 is singular or plural (the 들이, which would indicate a plural state, is only sometimes specified in Korean). To translate this ‘accurately’ would be to create uncertainty and doubt in the mind of the English-language reader, and thus in translation the town names named (appropriate specificity and no Eastern-European ‘uncanniness’) and children’s locations are explicity determined

Another strategy Kim uses is to add information which is not present in the source text. She does this in two ways, sometimes as a form of explication, and sometimes to add specificity that does not exist in the Source Text. Perhaps the second strategy is the more interesting one.

On page 16 of the Korean text (11th line) a scene occurs at Seoul Station:

엄마를 잃어버린 장소로 가는 사이 수많은 사람들이 네 어깨를 치고 지나갔다.

(So many people go by, brushing your shoulders, as you make your way to the spot where Mom was last seen.)

Which is translated to something extremely more specific by Kim Chi-young (Page 9, 19th Line):

So many people go by, brushing your shoulders, as you make your way to the spot where Mom was last seen. You look down at your watch. Three o’clock. The same time Mom was left behind.

That this is an ‘unimportant’ detail is confirmed by the next sentence, both in Korean and English, which has no relationship to, or need for, the added detail:

아버지가 엄마 손을 놓친 자리에 서 있는 동안에도 사람들은 네 어깨를 앞에서 뒤에서 치고 지나갔다.

(People shove past you as you stand on the platform where Mom was wrenched from Father’s grasp.)

A very similar change is made later in the book when discussing the narrator’s book and its Braille version. The Korean reads (Page 41, 6th Line):

점자로 만들어진 너의 책이 호명되고 너는 그 책을 받으러 앞으로 나갔다. 도서관장의 손을 통해 네게 전달된 책은 판형이 기존의 책보다 두배는 큰데 가벼웠다.

(They spoke about your book, and you went to the front to receive the Braille version. The books given to you by the director were twice as big as yours, but they were light.)

While the English version adds a kind of specificity that is absent in the original (Page 33, 20th Line):

They spoke about your book, and you went to the front to receive the Braille version. Your one book became four volumes in Braille. The books given to you by the director were twice as big as yours, but they were light.

Even larger changes are made in paragraph order, as the following examples show (From 10th line of page 16 to 14th line of page 17), with the changes in order indicated by bold text:

Years ago, a few days before you left your hometown for the big city, Mom took you to a clothing store at the market. You chose a plain dress, but she picked one with frills on the straps and hem. “What about this one?”

“No,” you said, pushing it away.

“Why not? Try it on.” Mom, young back then, opened her eyes wide, uncomprehending. The frilly dress was worlds away from the dirty towel that was always wrapped around Mom’s head, which, like other farming women, she wore to soak up the sweat on her brow as she worked.

“It’s childish.”

“Is it?” Mom said, but she held the dress up and kept examining it, as if she didn’t want to walk away.

“I would try it on if I were you.”

Feeling bad that you’d called it childish, you said, “This isn’t even your style.”

Mom said, “No, I like these kinds of clothes, it’s just that I’ve never been able to wear them.”

How far back does one’s memory of someone go? Your memory of Mom?

Since you heard about Mom’s disappearance, you haven’t been able to focus on a single thought, besieged by long-forgotten memories unexpectedly popping up. And the regret that always trailed each memory.

I should have tried on that dress. You bend your legs and squat on the spot where Mom might have done the same. A few days after you insisted on buying the plain dress, you arrived at this very station with Mom.

And as translated:

How far back does one’s memory of someone go? Your memory of Mom?

Since you heard about Mom’s disappearance, you haven’t been able to focus on a single thought, besieged by long-forgotten memories unexpectedly popping up. And the regret that always trailed each memory.

Years ago, a few days before you left your hometown for the big city, Mom took you to a clothing store at the market. You chose a plain dress, but she picked one with frills on the straps and hem. “What about this one?”

“No,” you said, pushing it away.

“Why not? Try it on.” Mom, young back then, opened her eyes wide, uncomprehending. The frilly dress was worlds away from the dirty towel that was always wrapped around Mom’s head, which, like other farming women, she wore to soak up the sweat on her brow as she worked.

“It’s childish.”

“Is it?” Mom said, but she held the dress up and kept examining it, as if she didn’t want to walk away.

“I would try it on if I were you.”

Feeling bad that you’d called it childish, you said, “This isn’t even your style.”

Mom said, “No, I like these kinds of clothes, it’s just that I’ve never been able to wear them.”

I should have tried on that dress. You bend your legs and squat on the spot where Mom might have done the same. A few days after you insisted on buying the plain dress, you arrived at this very station with Mom.

These changes are quite drastic, and yet to look at them is to see that they were made in order to “fit” Western narrative style. In fact, two ‘problems’ are addressed here at the same time. First, Western language resides in a low context culture, while Korean is resolutely high context. This means that the Western reader, by cultural affinity, will expect a narrative to be more linear and well defined than an Eastern reader might. This difference, in fact, underlies many of the ‘translations’ made by author Shin and translator Kim, and here it is quite obvious. The English text has been rearranged in such a way that the narrative line is clearer – the philosophical question which the passage asks, ‘how far back does a ‘mother’ go,’ is turned from a conclusion to a headline, and in this way the Western reader is alerted to the meaning of the passage in the ‘normal’ structure the reader expects.

What do all these kinds of changes add up to, and given that the example used here is genre fiction, what implications might the success of the translation of Please Look After Mom (In the UK, Please Look After Mom, just another “translation” difference, even among the shared language of English) have for translation in general? I would suggest two things. First, it seems clear as a reader sorts through the ‘translations’ made by Kim Chi-young that they were all made with a keen understanding of both the requirements of genre and the textual expectations of potential readers. Second, it seems clear that this was one of the many reasons for the unprecedented success of the book. The fact that Please Look After Mom conformed, in all ways, to the expectations of the reading audience was instrumental in its success, even including its inclusion as an Oprah Book Club selection. Was something “lost” in translation, or even more alarming, was something else “gained?” Certainly so, but that is the price, not only of translation, but of reading, and that price seems worth paying if it results in a broader exposure of Korean literature to the English speaking world.

Finally, for the purists who decry the alterations made in the forms of translation discussed here, this paper offers a final comforting thought. When the “altered” version of Please Look After Mom was a success, the general popularity of Korean fiction (as measured on Amazon) rose approximately 15%, and the same was true when the “altered” version of Kim Young-ha’s Your Republic is Calling You was published (although, for various reasons, the increase in popularity of general Korean translated literature was slightly larger in the case of Kim Young-ha). This suggests that, perhaps paradoxically, a Skopos-based, Uncanny-Valley leaping translation strategy might eventually have the effect of eliminating the Uncanny-Valley for literature – as it brings a reader a comfortable, genre-based collection of books to read, it also introduces that reader to a new ‘look’ at Korean fiction, and in that way may promise to erase, or substantially reduce, the size of the Uncanny Valley between the cultures.