The Poet is the fourth work of Yi Mun-yol reviewed here. A paltry number, but the final number, because as far as I can determine, it is the total of his work translated into English.

I had the ‘traditional’ introduction to Yi: I read Our Tortured Hero. This is the work that most Koreans would recommend, of course, because it is a parable of Korean suffering in the modern era. It is good, but the least of his translated works. Then it was An Appointment With My Brother, a good story, but semi-predictable pundan munhak redeemed by Yi’s clever writing. Next, I read Twofold Song, which gave me the idea that Yi was more than a mere re-teller of recent historical suffering. Reading The Poet, which fuses the storytelling of Twofold Song with the historicity of Our Twisted Hero, makes me think he is a truly great writer.

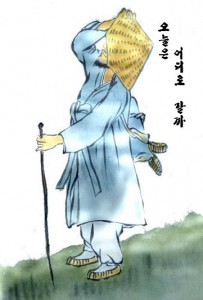

The novel concerns a historical figure, the 19th century Korean poet Kim Pyong-yon (better known as 김삿갓 for his signature bamboo hat). His grandfather, Kim Ik-sun was a traitor – originally captured by rebels he became their ally and was eventually executed when the rebellion failed (in other versions he was merely unconsciously drunk, but his fate was the same either way). As Korean custom dictated that responsibility fell down the family line, Kim Pyon-yon was also persecuted.

This story might well have been interesting to Yi Mun-yol, as Yi’s father had been a communist and was thus seen as a traitor to South Korea. Yi’s father defected to North Korea in 1951. One hesitates to speculate how that adventure ended. In modern South Korea as in ancient, the sins of the father were passed down to the children and Yi lived a life that he must have identified with the story of Kim Sakkat.

As The Poet continues, it becomes clear that Kim will never be able to clear his name, and he becomes a wandering poet. At first he sponges off provincial officials and scholars, writing poems he knows will appeal to them. When he wears out his welcome there, he becomes a poet of the people, turning his back on conventional poetic and social structures. This wears thin as well, and Kim Sakkat becomes introspective, a poet of nature. At one point he is captured by rebels, and in an echo of his grandfather’s life, becomes enamored of them and writes poetry of and for them.

Yi Mun-yol describes each of these changes well, and often the change is caused by a meeting with a stranger, which turns Kim Sakkat’s life in its new direction. For instance, Sakkat leaves his family after he wins a poetry competition in which he writes a poem castigating his grandfather, and is afraid to go to the awards ceremony, lest his ancestry be known. Drinking in a bar, he meets a wandering poet who initially praises Sakkat’s poem, but then turns viciously on Sakkat when discovering that the poem is a breach of filial propriety.

The writing style is snaky and clever. Yi begins as a “distant” omniscient third person narrator who invokes a

conceit I rarely see in English literature except in the semi-snarky “dear-reader” formulation. Yi’s narrator is extremely intrusive and judgemental, yet Yi makes this work. Multiple themes lace through the novel, loyalty to family versus loyalty to state, the corruption but inevitability of state power, and the untrustworthiness of memory. Early on the narrator introduces the idea of “pseudo memory” and toys with the role of memory and historical ‘knowledge’ throughout the book. Yi also explores a Korean version of the idea of “original sin” as Sakkat cannot elude the judgment on his grandfather – wherever he goes it follows him. As noted earlier, this theme no doubt had resonance for Yi, given that his father’s defection to the North followed Yi.

Yi’s ability to thread these themes without cost to the narrative, his skill at giving the reader understanding of the forces and vagaries that push Sakkat from role to role and place to place, and his clever writing and narrative stance make this book a classic, both in Korean (I am told) and in English (as I can attest).

The translation is excellent. The reliable Brother Anthony of Taize works with Chung Chong-Wha to produce an eminently readable text that clearly brings out the semi-sardonic tone of the narrator as he(?) examines the historical record and historical wreckage. The volume includes 8 pages of footnoted explication that I found supernumary – most of what it explains is fine, but it is not necessary to understand the book, and I can’t imagine why I would flip back to the appendix to, for instance, get the definition of kisaeng, when its meaning is abundantly clear from context.

A great book, from a great writer. I certainly hope that someone out there is busy translating more of Yi Mun-yol’s work.

NOTE: Title of “Our Twisted Hero” has been changed to reflect reality. 😉