Bae Su-ah’s (whose Wikipedia page,we massively re-created in October 2013) Highway With Green Apples is a melancholic tale. With that said, it seem particularly suited for certain kind of reader, both in Korea and abroad, in English we might put it in the genre or relationship or women’s fiction and fans of those kinds of stories will find this one very satisfying and, perhaps, a bit bleak; for Bae there is no Prince Charming waiting and at least one simple household item becomes the symbol of that bleakness. The narrator in this story is essentially unmoved by love, sex, or anything having to do with the future, except, perhaps (and it is a “perhaps”) the idea of stepping entirely outside of the rat-race she lives in. The novella (about 47 pages) is available of a puny $1.99 on Kindle, and at a price like that, how you can you afford not to buy a meditation on the position of single “late” (or so she feels, explaining herself as: ““I am one week away from my twenty-fifth birthday. I hate being that age. That age is neither as fresh and full of life as fifteen years nor as jaded as the afternoon of thirty-five years.”) young women (^^

Bae Su-ah’s (whose Wikipedia page,we massively re-created in October 2013) Highway With Green Apples is a melancholic tale. With that said, it seem particularly suited for certain kind of reader, both in Korea and abroad, in English we might put it in the genre or relationship or women’s fiction and fans of those kinds of stories will find this one very satisfying and, perhaps, a bit bleak; for Bae there is no Prince Charming waiting and at least one simple household item becomes the symbol of that bleakness. The narrator in this story is essentially unmoved by love, sex, or anything having to do with the future, except, perhaps (and it is a “perhaps”) the idea of stepping entirely outside of the rat-race she lives in. The novella (about 47 pages) is available of a puny $1.99 on Kindle, and at a price like that, how you can you afford not to buy a meditation on the position of single “late” (or so she feels, explaining herself as: ““I am one week away from my twenty-fifth birthday. I hate being that age. That age is neither as fresh and full of life as fifteen years nor as jaded as the afternoon of thirty-five years.”) young women (^^

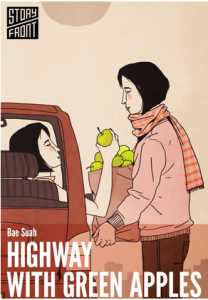

The narrator of Highway With Green Apples has just broken up with a boyfriend just after a trip on which they bought green apples from a roadside vending-woman. Her mind, both consciously and through the actions and seemingly unrelated thoughts) compares the simplicity of that vending life to the complication and confusion, essentially meaningless, of the life of the 888.800 generation (I’m not sure I have that generation right, but leave it out here for readers to respond to and correct). The narrator is a dropout, estranged from her family, and apparently without any strong personal relationships.

Apples moves seamlessly between the simple past, past-progressive and simple present, often in the same scenes (Kudos to translator Sora Kim-Russell who handles this all with aplomb). In addition, as in many Korean novels, be aware of shifts in time and place, as the narrator moves around without formal notice that anything has changed. I sometimes wonder if Korean readers are better trained to pick up these subtle changes, and then I remember the difference between high and low context cultures, and it is clear to me that they very well might.

The narrator interweaves various stories of her history, introducing characters at seemingly random times, as though flipping through some sort of internal life-long yearbook. The scenes, themselves, are initially unremarkable – the purchase of apples, meeting to drink, friends re-uniting and so on. But somehow, truncheons of sentences translated into vernacular English manages to merge the feelings of routine and dread into a kind of quotidian hopelessness. Bae weaves things of no particular importance: weather, time of day, and banal conversations into a kind of mosaic of fear and loathing; the items of daily life become a frame of dread, or background painting, in which the narrator lives. About 75% of the way through the story, that mosaic begins to take its final shape.

The story is about limitations, clearly symbolized by Bae’s repeated emphasis on the small living spaces of many of the characters and how their jobs and lives end up completely trapping them. In this way it is a bit reminiscent of Christmas Specials by Kim Ae-ran, The Cave by Kim Mi-wol, and Apartments by the venerated Park Wan-suh, as well many other Korean short stories. Interestingly, as I look at that list I realize these are all female authors and wonder if there is some causation here. I leave it to a commenter less lazy than I to provide the cause and effect (I dunno, you might start with ‘glass ceiling’, but who am I to say?).

The translation, but Sora Russell Kim, is crisp and effective, and without knowing the work in its original language I can only judge by the English, which is spot on in terms of its vernacular (“grease monkey”) and contains some nice renditions of deadpan lines

“I remember the guy. …. He wasn’t particularly memorable.”

“A Cousin isn’t something solid. Neither is a family” (this may seem more clear as a deadpan joke to those familiar with some aspects of Korean culture)

The story works well as a ‘Korean story’ (particularly with it’s understood timetable under which the narrator lives – she should be getting serious about getting married and having children) but it also works well as a story of *any* person in their mid-20’s in almost any first-world country – looking for meaning on which to build a future, and uncertain that either of those things exists.

Again, 47 pages, good read, downloads straight to your Kindle. Have at it!